Using the Basic Ginga Viewer Object in Python Programs

The core design principle of the Ginga project is to make it possible to easily build powerful image viewers in Python with many possible GUI toolkits.

This chapter is for developers who want to use only the Ginga rendering class in a program of their own design (not customizing the reference viewer).

Using the basic rendering class in new programs

Ginga basically follows the Model-View-Controller (MVC) design pattern,

that is described in more detail in the chapter on internals

(see Ginga Internals).

The “view” classes are rooted in the base class ImageView.

Ginga supports backends for different widget sets through various

subclasses of this class.

Typically, a developer picks a GUI toolkit that has a supported backend

(Gtk 3, Qt 5/6, Tk, matplotlib, HTML5 canvas) and writes a GUI program

using that widget set with the typical Python toolkit bindings and API.

Where they want a image view pane they instantiate the appropriate

subclass of ImageView (usually a CanvasView), and using the

get_widget() call extract the native widget and insert it into the

GUI layout. A reference should also be kept to the view object, as this

is typically what you will be calling methods on to control the viewer

(see Ginga Image Viewer Operations).

Ginga does not create any additional GUI components beyond the image

pane itself, however it does provide a standard set of keyboard and

mouse bindings on the host widget that can be enabled, disabled or

changed. The user interface bindings are configurable via a pluggable

Bindings class which constitutes the “controller” part of the MVC

design. There are a plethora of callbacks that can be registered,

allowing the user to create their own custom user interface for

manipulating the view. Of course, the developer can add many different

GUI widgets from the selected toolkit to supplement or replace these

built in controls.

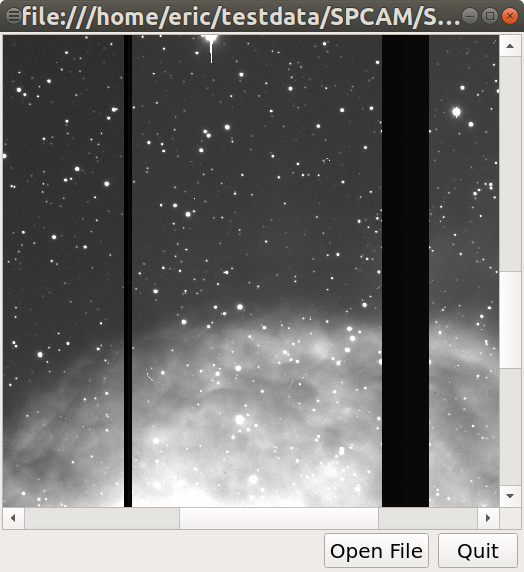

A simple, “bare bones” FITS viewer written in Qt.

Listing 1 shows a code listing for a simple graphical FITS

viewer built using the subclass CanvasView from the module

ImageViewQt (screenshot in Figure A simple, “bare bones” FITS viewer written in Qt.) written in

around 100 or so lines of Python. It creates a window containing an

image view and two buttons. This example will open FITS files dragged

and dropped on the image window or via a dialog popped up when clicking

the “Open File” button.

#! /usr/bin/env python

#

# example1_qt.py -- Simple FITS viewer using the Ginga toolkit

# and Qt widgets.

#

import sys

from ginga.misc import log

from ginga.qtw.QtHelp import QtGui, QtCore

from ginga.qtw.ImageViewQt import CanvasView, ScrolledView

from ginga.util.loader import load_data

class FitsViewer(QtGui.QMainWindow):

def __init__(self, logger):

super(FitsViewer, self).__init__()

self.logger = logger

# create the ginga viewer and configure it

fi = CanvasView(self.logger, render='widget')

fi.enable_autocuts('on')

fi.set_autocut_params('zscale')

fi.enable_autozoom('on')

fi.set_callback('drag-drop', self.drop_file)

fi.set_bg(0.2, 0.2, 0.2)

fi.ui_set_active(True)

self.fitsimage = fi

# enable some user interaction

bd = fi.get_bindings()

bd.enable_all(True)

w = fi.get_widget()

w.resize(512, 512)

# add scrollbar interface around this viewer

sw = ScrolledView(fi)

vbox = QtGui.QVBoxLayout()

vbox.setContentsMargins(QtCore.QMargins(2, 2, 2, 2))

vbox.setSpacing(1)

vbox.addWidget(sw, stretch=1)

hbox = QtGui.QHBoxLayout()

hbox.setContentsMargins(QtCore.QMargins(4, 2, 4, 2))

wopen = QtGui.QPushButton("Open File")

wopen.clicked.connect(self.open_file)

wquit = QtGui.QPushButton("Quit")

wquit.clicked.connect(self.quit)

hbox.addStretch(1)

for w in (wopen, wquit):

hbox.addWidget(w, stretch=0)

hw = QtGui.QWidget()

hw.setLayout(hbox)

vbox.addWidget(hw, stretch=0)

vw = QtGui.QWidget()

self.setCentralWidget(vw)

vw.setLayout(vbox)

def load_file(self, filepath):

image = load_data(filepath, logger=self.logger)

self.fitsimage.set_image(image)

self.setWindowTitle(filepath)

def open_file(self):

res = QtGui.QFileDialog.getOpenFileName(self, "Open FITS file",

".", "FITS files (*.fits)")

if isinstance(res, tuple):

fileName = res[0]

else:

fileName = str(res)

if len(fileName) != 0:

self.load_file(fileName)

def drop_file(self, fitsimage, paths):

fileName = paths[0]

self.load_file(fileName)

def quit(self, *args):

self.logger.info("Attempting to shut down the application...")

self.deleteLater()

def main(options, args):

app = QtGui.QApplication(sys.argv)

# ginga needs a logger.

# If you don't want to log anything you can create a null logger by

# using null=True in this call instead of log_stderr=True

logger = log.get_logger("example1", log_stderr=True, level=40)

w = FitsViewer(logger)

w.resize(524, 540)

w.show()

app.setActiveWindow(w)

w.raise_()

w.activateWindow()

if len(args) > 0:

w.load_file(args[0])

app.exec_()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(None, sys.argv[1:])

Looking at the constructor for this particular viewer, you can see where

we create a CanvasView object. On this object we enable automatic

cut levels (using the ‘zscale’ algorithm), configure it to auto zoom the

image to fit the window and set a callback function for files dropped on

the window. We extract the user-interface bindings with

get_bindings(), and on this object enable standard user interactive

controls for all the possible key and mouse operations.

We then extract the platform-specific widget (Qt-based, in this case) using

get_widget() and pack it into a Qt container along with a couple of

buttons to complete the viewer.

Scanning down the code a bit, we can see that whether by dragging and

dropping or via the click to open, we ultimately call the load_file()

method to get the data into the viewer. load_file() creates

an AstroImage object (the “model” part of our MVC design), which is

then passed to the viewer via the set_image() method.

AstroImage objects have methods for ingesting data via a file path, an

astropy.io.fits HDU or a bare Numpy data array. For a reference

on the model, see here:ref:_ch-image-data-wrappers.

Many of these sorts of examples for all supported backends are contained

in the examples directory in the source distribution.

For a list of many methods provided by the viewer object see

this reference Ginga Image Viewer Operations. You can also click on the

module index link at the top of this chapter and then click on the link

for ImageViewBase.

Graphics plotting with Ginga

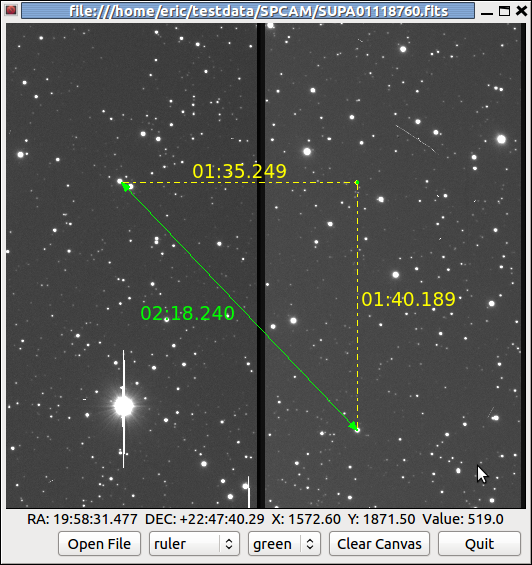

An example of a CanvasView widget with graphical overlay.

A CanvasView actually pairs a view with a canvas object (in

particular a DrawingCanvas object). You can get more detail about

canvases and the objects they support (see Ginga Canvas Graphics).

A variety of graphical shapes are available, and plotted objects scale,

transform and rotate seamlessly with the viewer.

Rendering into Matplotlib Figures

Ginga can also render directly into a Matplotlib Figure, which opens up possibilities for overplotting beyond the limited capabilities of the Ginga canvas items. See the examples under “examples/matplotlib” for ideas, particularly “example4_mpl.py”.

Rendering into HTML5 canvases

Ginga can render onto HTML5 canvases displayed in a web browser. This opens up interesting possibilities for server-based remote viewing tools. See the examples under “examples/pg”, particularly “example2_pg.py”.

Writing widget toolkit independent code

You can write code that allows the widget set to be abstracted by Ginga’s widget wrappers. This is the same technique used to allow the reference viewer to switch between supported toolkits using the “-t” command line option. Currently only Qt (5/6), Gtk (3), and HTML5 (to a more limited degree) are supported, and there are some limitations compared to developing using a native toolkit directly. Nevertheless, the ability to target different platforms just by changing a command line option is a very interesting proposition.

See the examples under “examples/gw”, particularly “example2.py”.